Dan Starks: Vietnam Veterans, "Thank you."

By Dan Starks, Founder and Chairman, National Museum of Military Vehicles

Vietnam Veterans: Thank you.

Join Dan Starks, founder of the National Museum of Military Vehicles, in a special edition of the Founder's Forum, focusing on Vietnam veterans. This video offers a deep dive into their experiences, challenges, and the historical impact of their service. Topics include tributes to veterans, insights into combat realities in Vietnam, perspectives of the North Vietnamese forces, the effects of Agent Orange, and the societal reception of returning veterans. The video also highlights the museum's role in preserving and educating about this chapter of American history. It serves as a tribute to the bravery and sacrifices of Vietnam veterans, encouraging viewers to engage, visit the museum, and subscribe for more content on military history.

Transcript of video:

I'm Dan Starks, founder of the National Museum of Military Vehicles. Welcome to this edition of Founders Forum. The theme for this video is tribute to our Vietnam veterans.

One of our mantras here at the museum is we strive to make every single day Veterans Day, every single day Memorial Day, and I want to do that in the next minutes in this videotape. And with all kinds of different thoughts, the Vietnam veterans know what they did in combat during their deployment to Vietnam, but not very many Vietnam veterans realize the history that they've created and really realize how now that Vietnam, the Vietnam War is out of current events, what's their legacy? So I want to talk both to Vietnam veterans and to their families as well as to everyone who's come along here who, after the Vietnam War or people like me who lived during the Vietnam War but did not provide military service, I want to talk about what a big deal it was for our Vietnam veterans and how much they did, how successful they were on the battlefield, how much they sacrificed, and how poorly we treated our Vietnam veterans when they returned home, all with the idea not to beat on ourselves, but all with the idea that it's not too late for us to take small steps to make things a little better for our Vietnam veterans. So that's the goal of everything that's going to come next.

I've got an algorithm in my mind that I want to follow. The first thing is to talk about how tough combat was for Americans serving in Vietnam. A lot of people don't realize how tough our adversary was in the Vietnam War.

And when I think about our adversary, we talk about the Viet Cong, which were really insurgents, guerrilla warfare style, members of South Vietnam blended in with the population. One of the dilemmas for Vietnam veterans and deployed to Vietnam was they didn't know who was going to try to kill them, who was going to try to maim them, who was going to try to hurt them, just all blending in with the population. So that's the Viet Cong.

The part of our adversary that I really want to focus on, though, is the North Vietnamese Regular Army, the NVA. So yeah, it's NVA and it's Viet Cong. But the NVA was just an extremely experienced, combat-hardened adversary with far more combat experience than any American who deployed to Vietnam to fight the North Vietnamese Regular Army.

Just think about the legacy in Vietnam. The North Vietnamese had multi-generational combat experience. The North Vietnamese fought the Japanese during World War II.

Jungle warfare, their first introduction to modern warfare against an enemy with superior firepower, the Vietnamese, the North Vietnamese Regular Army came out of the World War II experience very combat capable. They immediately jumped into a war against the French, the so-called French Indochina War. When Vietnam declared independence at the end of World War II, as the Japanese were now going to...were now in the process of withdrawing from Vietnam, Vietnam declares independence, and the French say, you can't be independent.

The French had got the benefit of the Allies, really underscoring the principle that every people are entitled to govern themselves, the so-called right of self-determination. We liberated France from dominance by Nazi Germany. The French are paying lip service to vindicating the right of self-determination, except when it came to Vietnam and other former French colonies.

So when the Vietnamese say, self-determination, we'll manage ourselves going forward, the French said, no, we're sending our army into Vietnam to stop you from becoming independent. You have to become a French colony again. So that's the first...that's the French Indochina War.

Began immediately following the end of World War II and continued until the French were defeated at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954. As a result of that defeat of the French, the French negotiated the Geneva Accords with the Vietnamese, agreeing that there would be a two-year transition period at the end of which the French would completely withdraw from Vietnam, granting Vietnam its independence, and then there would be national elections to determine the new Vietnamese government for Vietnam. But the point that I wanted to make, not so much the history, the point I wanted to make was that the North Vietnamese were in combat all those years against the French military with substantially superior firepower, and the North Vietnamese perfected their tactics, not only for jungle warfare, but for fighting against an adversary with an overwhelming superiority in firepower.

French leave at the end of 1956, the United States fills that vacuum. My point is not to talk about the politics or to talk about really the history of Vietnam. My point is just to talk about the combat experience of the adversary that we faced when we sent American ground troops into Vietnam.

So we weren't fighting a neophyte. We were fighting people that had generational experience of combat in jungle warfare, generational experience in combat against adversary with superior firepower. So here we've got Americans deployed to Vietnam.

Now, most Americans who deployed to Vietnam were deployed for one tour. A number of Americans were deployed for multiple tours, but there's not a single American who deployed to the battlefield in Vietnam who had as much combat experience as these professional adversaries who had spent year after year after year of their lives in combat against the Japanese, then against the French, and now against the Americans. That's the first thing.

The second thing is we would think about jungle warfare. Think about the background of every single American who deployed to Vietnam. We had diverse backgrounds, but I can tell you for all practical purposes, no Americans had a background in jungle warfare.

So we've got inner city kids. We've got other urban Americans. We've got suburban Americans.

We have Americans who came from small towns and rural settings. But for all practical purposes, we didn't have any Americans who grew up in a jungle and who had worked out optimum tactics for jungle warfare. So they've got more combat experience and they are on the home court.

We are fish out of water. Our Vietnam veterans were fish out of water as they entered the battlefield against this very tough adversary. Now, and the next thing to point out would be how many different combat environments our Vietnam veterans had to step up and figure out how to engage in.

You think about jungle warfare. Well, we had to engage in tunnel warfare. The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong had just extensive underground bunker and tunnel systems and safe havens, underground hospitals, underground kitchens, underground recreation centers.

They just had all that worked out. And that's just one scenario. We also had to figure out helicopter warfare.

We didn't have prior significant experience with helicopter warfare. We also had to figure out for the first time in a hundred years, for the first time since the American Civil War, we had to figure out river combat. The American military had not engaged in river combat since the American Civil War ending in 1865.

And now here we don't have the boats to do it with. We don't have the tactics worked out. We don't have the training on how to do it.

Our Vietnam veterans had to just figure it out in combat on the fly with their lives at stake. Add to that rice paddy warfare, add to that mountain warfare, add to that the urban warfare, which typically you don't think about Vietnam as involving urban warfare. We had fierce urban combat, particularly surrounding the 1968 Tet Offensive.

We had substantially a full month of combat in the former capital city of Hue, the battle where we took more casualties than any other battle, 1,800 American casualties. Not a single American in that fight had any significant training or experience in urban combat. And yet here they are in the same kind of really absolute total urban combat.

They characterize the fiercest urban fighting of World War II. We had to go room to room, building to building, block to block for almost a full month to clear the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong from the city of Hue after they took it over on the first day of the 1968 Tet Offensive. And we had with our Vietnam veterans, I say our, I'm talking about our Vietnam veterans, with Vietnam veterans' lives at stake, they had to wing it.

They had to figure it out on the fly, how to do something that none of them expected to have to face. And that same scenario held true with lesser degrees of severity in numerous population centers during the 1968 Tet Offensive. So our Vietnam veterans are fighting a very tough adversary, point one, point two, we're fighting a tough adversary in really difficult and diverse difficult combat conditions.

Now, how did we do? How did our Vietnam veterans do in that kind of scenario? It would be a tremendous mistake to have the absolute wrong idea that our Vietnam veterans lost on the battlefield in Vietnam. Yes, after, at a political level, we ended up withdrawing from Vietnam. That had nothing to do with battlefield success of our Vietnam veterans.

We ended up withdrawing as a result of a political calculation. After we withdrew, our adversary ended up taking over South Vietnam. This is very analogous to what happened in Afghanistan, more familiar to most people that are watching this video in Afghanistan on the battlefield.

American combat veterans won absolutely every major battle, and they accomplished every major military goal given to them. The fact that subsequently we withdrew, and subsequently the Taliban took over, takes nothing away from the battlefield success of every Afghanistan combat veteran. Exactly the same for our Vietnam combat veterans.

On the battlefield, every single Vietnam veteran came home a winner. Critical point. So we won on the battlefield in tough circumstances.

What did it cost our Vietnam veterans to win every major battle and accomplish every major combat objective and mission given to them on the battlefield? What did it cost them? What do you think our casualty rate was overall for our Vietnam veterans? Get a number in your mind. I'm expecting to shock you saying our casualty rate was about a one-third casualty rate. Now, that's not what the American people, that's not in the consciousness of the American people.

The Americans deployed to Vietnam suffered a one-third casualty rate, but those are the facts. And here's the numbers to get there. A lot of people know we have a little over 58,000 names on the Vietnam Memorial Wall, Americans deployed to Vietnam who lost their lives in Vietnam, over 58,000.

So that number's well-known. Less well-known is how many major combat wounded do we have to add to the battlefield deaths? And we show here at this point at the end of the display, at the end of the Vietnam War Gallery, we have a number of 153,000 Americans wounded. Now, our data show that we issued about 300,000 Purple Hearts to Vietnam veterans.

We're not using the number of 300,000, we're using a number about half that. Our research shows that of the 300,000 or so Purple Hearts awarded, 153,000 of those Purple Hearts were awarded to Vietnam veterans wounded severely enough to be hospitalized with their wounds. So a very conservative interpretation of the data, 153,000 wounded to add to the more than 58,000 dead.

So more than 200,000 casualties. The casualty category that people don't think to add that has to be added is our Agent Orange casualties. Now, when you come to the museum, we go through the story of our poisoning Vietnam veterans by spraying them with 20 million gallons of Agent Orange and denying that it was going to hurt them, knowing all the time that Agent Orange has an extremely deadly poisonous form of dioxin that can kill a human being with exposure to trace amounts as little as three or four parts per million.

So we spread from 1962 until 1971, we spray Agent Orange on Americans deployed to Vietnam. And when they come home, once the war is over, we have Vietnam veterans dying at significantly higher rates than the rest of the American population. We gaslighted them, we stonewalled them from the time we started spraying Agent Orange in 1962 until 1991.

We denied that their disabilities, we denied that their deaths, we denied that there was any connection between them as casualties and their deployment to the Vietnam War until finally 1991, we passed the Agent Orange Act of 1991, come and claim and acknowledging, yeah, although we denied it for three decades, it's absolutely true that this is due, you're an Agent Orange casualty. Now, since the Agent Orange Act of 1991, our research shows more than 650,000 Vietnam veterans have been treated as Agent Orange casualties. Now, saying that we've treated them doesn't mean that they got better.

A lot of Agent Orange casualties died in spite of treatment. Those who didn't die were often every bit as debilitated for the rest of their lives as any other Vietnam veterans severely wounded on the battlefield. You've got to add our Agent Orange casualties, even though none of those names appear on the memorial wall and none of those Americans were recognized with a purple heart as a result of the physical harm they suffered in the combat environment on the battlefields in Vietnam.

And this 650,000 is an undercount. It's a big undercount. 650,000 is how many were treated.

And nobody was treated as an Agent Orange casualty until 1991. So we don't have data for how many Americans returned from Vietnam, came to qualify as an Agent Orange casualty, but wasn't treated and then died of any reason. They might've died of Agent Orange.

They might've died of anything else prior to the Agent Orange Act of 1991. So big undercount, but at least 650,000 need to be added to that more than 200,000. So we're above 850,000 casualties among Americans who deployed to Vietnam.

Now you got to add one more category of casualties, PTSD casualties, post-traumatic stress casualties. The battlefields of Vietnam, as you come and walk through our efforts to immerse visitors into the combat experience of Vietnam veterans here at the museum, that battlefield was just traumatic from all kinds of multiple sources. And a high amount of Americans who returned from Vietnam to here to the United States came with emotional scars, emotional debilitation, post-traumatic stress, and right to this day.

And you've got to add our post-traumatic stress casualties to these other three categories of casualties. Now we don't have, our research doesn't give us a total of Vietnam veterans who returned home suffering from post-traumatic stress. We have a VA number for how many Vietnam veterans are still suffering from post-traumatic stress in 2019.

That number is 271,000. Now, so since we just don't have, instead of making up a number or estimating a number, we use this number of 271,000, knowing it's far too small. It doesn't include anybody who returned from Vietnam suffering from post-traumatic stress who died of any reason prior to 2019.

So there's it's, total numbers gotta be something like four or five times the number we use of 271,000. But even using 271,000, add that to this more than 850,000 casualties we've already calculated. And this cumulates to somewhere between 1.1 million and 1.2 million casualties among our Americans deployed to Vietnam.

We show 3.4 million Americans deployed to Southeast Asia, not just Vietnam, deployed to Southeast Asia in the 20-year period beginning 1955 to our final withdrawal in 1975. And so that's a one-third casualty rate. Now, no group of American veterans except for our Vietnam veterans have suffered a one-third casualty rate, absolutely unprecedented.

They won on the battlefield in tough conditions and they paid a higher price as a group than any other group of American veterans in American history. So how did we treat our Vietnam veterans when they came home? You would think that if you add one and one, you get two. One, the first one is battlefield success.

The second one is level of sacrifice to gain all that success. You would think that would equal two. But in our history of treating our Vietnam veterans, it doesn't equal two.

When these Americans came home, after going through what they did, after prevailing on the battlefield like they did when they came home, not only did they not get a ticker tape parade, but they got abused and shunned. And I don't just mean anecdotally, I mean systematically. And it doesn't mean 100%, but I grew up in the Vietnam War era.

I was one year too young for the Vietnam War, for the draft. But I remember, I was aware I'm in on the news, I'm in on what's going on here with the Vietnam veterans, what's going on with the anti-war movement. And the national press coverage was, boy, this is really something because the anti-war protesters are organizing to make sure there are members of the anti-war movement at every major commercial port of entry for Vietnam veterans returning directly from the battlefield to the United States.

So in particular, San Francisco airport, Denver airport, Seattle airport. If Vietnam veterans came home through a military base, it was a different scenario. So I'm talking about the large number, the majority of Vietnam veterans who came home through commercial airports.

So they're a long time, only 48 hours out of combat. They got no decompression, no transition period, no support services. They're not even coming back with members of their own unit.

They're coming back with a plane load of other Vietnam veterans, none of whom know each other. They deployed under the individual replacement system. When their days of tour are up, they get on a truck, go to an airport, get picked up by a helicopter, go to an airport, and then they're flying back.

They're still all wound up. They haven't adjusted at all. They're in combat in their soul.

And they come into the airport and they've got survivor's guilt on the buddies they left behind at the combat base where the helicopter picked them up. And what the very first thing that happens, anti-war people, they don't know. Anti-war protesters rush up to them, spit in their face, call them baby killers, harass them, trying to provoke a reaction and trying to make that confused and stressful first experience back in the United States as miserable as possible.

Now imagine that you... So that's your airport reception. Now imagine you have gotten out of the airport and you're back home. Well, because of the political controversies about the war, you couldn't count on any kind of warm reception.

Now, a lot of Americans who were drafted, who would be drafted at age 18, and the two-year military commitment, they're back from Vietnam, they're 20 years old. They get the benefits of the GI Bill. They got drafted out of complete high school, they get drafted.

So now what are they going to do? A lot of Americans, of Vietnam veterans, wanted to take advantage of the GI Bill to get a college education. But if you're going to go on a college campus, that's a hotbed of anti-war protests. If you're a Vietnam veteran, 20 years old, going to enroll in college, you better not let people know you're a Vietnam veteran.

Not only do you not get honored and accoladed, not only is there not a tribute, not only is this not Veterans Day for you and Memorial Day for those that you left behind, but you'd better just stuff it. If people know you're a Vietnam veteran with the anti-war sentiment, you're not going to get a date. If they find out, you're not going to make friends.

If they find out, you're going to get harassed and abused. So just hide it. How would you like to engage in combat, have all kinds of consequences for the rest of your life from your military experience, and then not only not be thanked, not be honored, but stuff it, hide it like you did something shameful? That's what happened to so many of our Vietnam veterans.

And that's then where the Vietnam veteran experience ended for so many Americans still with us today as Vietnam veterans. Vietnam veterans are in their 70s. We've got a lot of Vietnam veterans among us.

We have a lot of immediate family of Vietnam veterans. And these are people who had what I've described happen to them. So that's where this museum comes in.

And that's where the tribute to Vietnam veterans episode here in the Founders Forum comes in. The only good thing about everything I've described is it's not too late to do the best we can to make amends with our Vietnam veterans. I've had Vietnam veterans ask me if I know what they say to one another when they meet a Vietnam, another Vietnam veteran for the first time.

It's just always stuck in my mind. I'm sure there's no one-size-fits-all here, but I've had more, you know, multiple Vietnam veterans say, when I meet another Vietnam veteran, we shake hands and say, welcome home, because nobody else ever did. How's that sit? So that's where the education and honor and service and sacrifice here at the museum comes in.

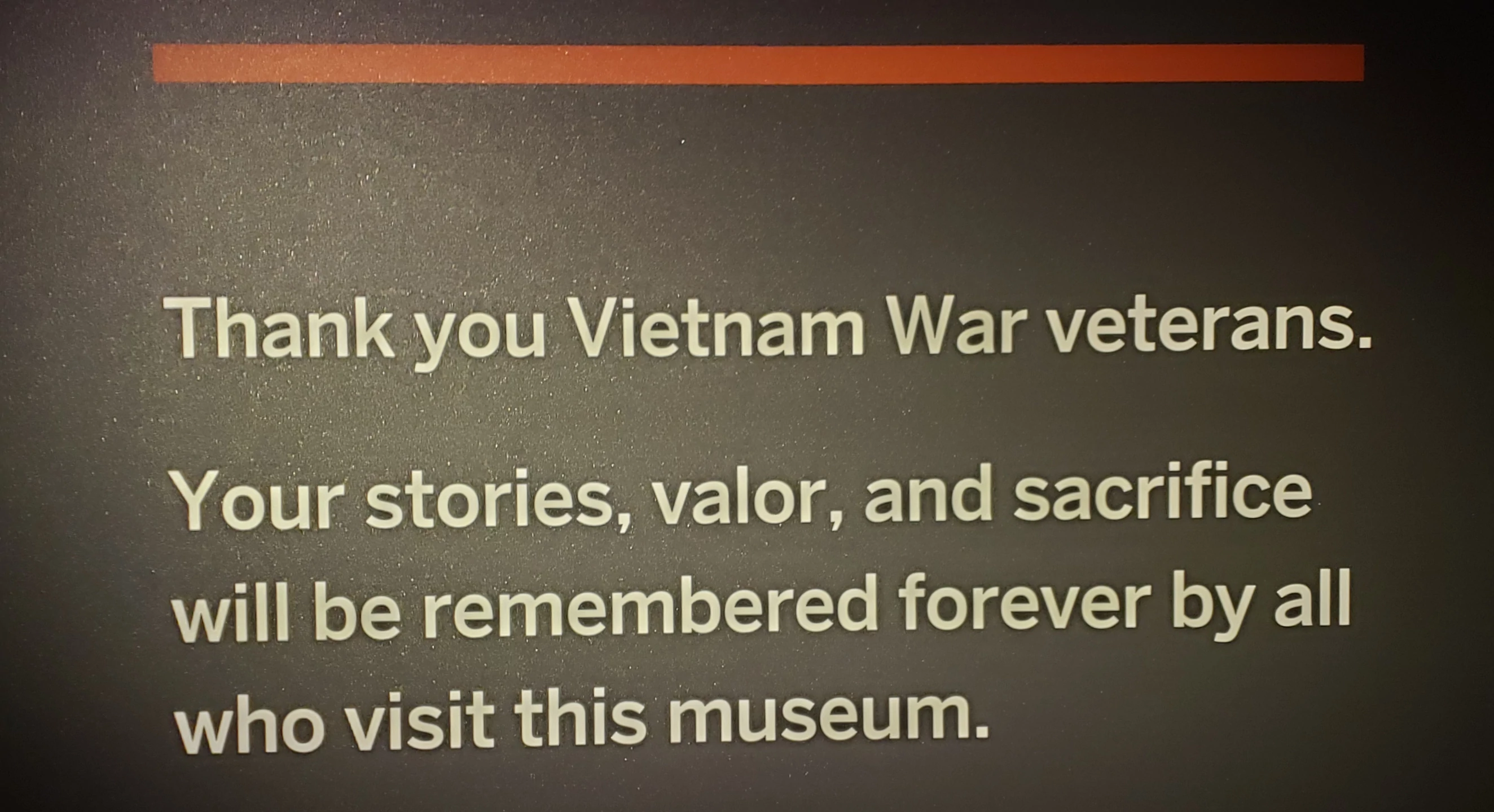

Vietnam veterans might think that what they did has been forgotten and that it has not been honored, that next generations won't learn about what they did. And what we do here at the museum is we tell every Vietnam veteran who comes through and every family member of every Vietnam veteran, you might think what you've done has been forgotten, but you're wrong. Your stories, your valor, and your sacrifice will be remembered forever by all who visit this museum.

All of us here can be dead, but your stories, valor, and sacrifice still will be passed along and remembered and honored by everyone who visits this museum. And when people come through without a tour, we've got signs that say exactly what I've just said, with spotlights shining on them. It doesn't make past rights wrong, but it is a step in the right direction to tell Vietnam veterans, thank you, welcome home, and what you did counts, and what you did will be honored and remembered and forever passed along.

If you visit the museum, you'll get everything I've just kind of said in a fast way in detail. And I invite all of you to come and take full advantage of everything we're offering here at the museum, but really this video itself is just standalone. Go hug a Vietnam veteran, go shake a hand of a Vietnam veteran, go thank a Vietnam veteran, and let them know that you that you have a little bit of sense of how tough it was, how well they did, how high a price they paid, and thank you.